Dark Kalm saw the last of the Lunar children settling to sleep. The ink-black sky, dotted with crystalline stars, was infiltrated by the orange-scarlet light rays cast out by The Solar as it slowly rose above the mountains. Shadows stretched almost painfully from their hosts; the palm-like cycad trees, and the many shrubs and bushes dotted about the plains. The river snaked through the land, glittering from both star and sunlight. A shard of The Sky Mirror, it wound away from the forbidding mass of green that was the jungle, in a slow meander through the thorn scrub and out into the distant desert, that shivered in a premature heat haze and was lit red as blood by The Solar’s light.

The patches of ground that were too dry to own moss remained hard and cracked from The Solar’s rays, like miniature jigsaw puzzles, and dust was swept up into the invisible arms of the breeze as it whispered through the land. Distant cries of winged reptiles, Pterosaurs, echoed over the terrain, and the last of the mammals squeaked as they resided in their holes in the ground. Dark Kalm faded into the pre-Solar-zenith, and, one by one, the children of The Solar rose from slumber.

Almost in an instant there was movement. The motionless shapes that had dotted the landscape began to get up and walk, prance or waddle off to the river or to graze. Hatchlings scampered restlessly about. insistent upon waking their drowsy parents, playing in the shrubs or up in trees, or in the shallower parts of the river that split the land in two. As The Lunar’s temporary reign ended, beaten back by The Solar, the herbivores and other animals of the day became active.

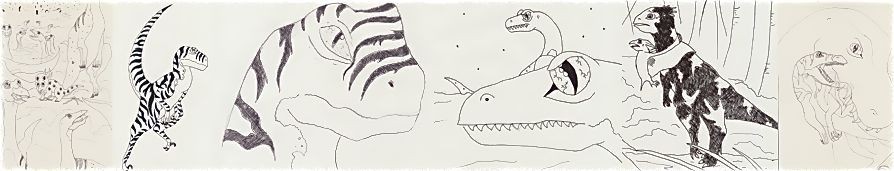

There were many herds in this territory; the emerald green, duck-billed Saurolophi, small, podgy grey Protoceratopi, and huge, long-necked Sauropods, Nemegtosaurs, to name but a few. There were winged Pterosaurs, gliding on the air currents over the land, their shadows sweeping across the ground, and also curious, feathered insectivorous dinosaurs, with eye patterns on their wings, just like butterflies.

As the pre-zenith progressed, the air buzzed not only with the heat, but with the sound of insects. The heat-hazes rose from the ground as the intense heat of the day increased, and cotton clouds drifted by, their shadows on the ground, beneath an azure sky. Dinosaurs resided beneath the shade of cycad-palms or shrubs, whilst others bathed in the shallow parts of the river, attempting to wash away the stifling heat.

One group of dinosaurs remained active, but only just. These were the feathered green insectivores, Avimimi, and they had trapped river water in their feathers to keep themselves cool. Feathered only along the arms, they used them as nets to capture insects, running towards swarms of flies or mosquitoes, and gleefully munching on their catches. But they were doing more than just acquiring breakfast.

The Avimimi in this territory were on patrol. They kept an eye on the boundaries of the land, should any new dinosaurs enter or leave, and reported it to their master, who lived in the mountain. They kept an eye on how many successful hatches or births there were in each herd, and generally watched over everything. There were about two hundred or so of them, each of them about the size of a terrier, and in small groups they went about their duties.

This year, the amount of successful births or hatches had been high. In almost every case, all the eggs that had been left in the nest (after the occasional theft by an Oviraptor) had hatched, and so far, only one head-butter had been born dead out of the many pregnant does in that herd. This was good news for everyone, and now the territory was dotted with babies, scampering after their parents or playing the odd game of “Rough and Tumble” with their brothers and sisters. The Avimimi were still working out roughly the amount of hatchlings there were, counting them in small groups to make it easier.

Avimimi were one of the few dinosaurs who knew how to count (other examples are Oviraptors and Protoceratopi), yet they could only count up to about six. Therefore, if every Avimimus counted at least six babies to every clutch, they did not know how much it was, but they knew it was a large number and therefore a successful year. They had managed to eventually teach their master to count, although he was not as intelligent as they, and so he too knew if it had been a successful year for the dinosaurs’ breeding.

The Avimimi were running after herbivores now, just like their hatchlings, taking a final check on how many offspring there were initially.

“Ah, right, Holly,” an Avimimus nodded as he confirmed the number, “one successful birth…‘Hodge’…right. What about you, Kripps? Did your mate’s birth go all right? Ah, I am sorry. Okay then, what about you, sir…”

“More than six babies, Molly!” one exclaimed, “Good grief! More than I can count! Well done – congratulations! Three bulls, three cows…and another cow…and another…”

At last they had finished, and headed back to the mountain to report the news to their master, now it was confirmed. They jittered excitedly to one another, stopping occasionally to gulp down insects, as they headed for the huge rock formation that loomed up before them.

The mountain was in fact an extinct volcano, silenced by The Lunar’s power millions of years ago. The very river that flowed through the land began here, as did many other rivers, yet they snaked off to other lands before meandering down to the sea. They began from the springs in the volcano’s side, hence why the land here was known as ‘Ignis Springs’. The volcano itself was known as Ignis Peak, and in Ignis Cave, about forty or fifty feet up its rocky yet flatter side, lived their master and ruler of Ignis Springs.

“How many hatchlings did you count?” An Avimimus asked the leader of the colony.

“I counted more than six sixes of baby Saurolophi,” he answered, “and I managed to count about five groups of six baby Nemegtosaurs. It’s been a good year, hasn’t it?”

“Indeed.”

They arrived at the foot of Ignis Peak, and began to climb, their nimble claws serving them well. There was plenty of foliage to hang on to, and the mountainside here was not very steep; it had to be quite a shallow gradient otherwise their master would not be able to climb it. They passed nests of Pterosaurs on the rocks, and a couple of head-butters – Homalocephali – as they made their way up to the cavern.

“Whose turn is it to wake him up?” the second Avimimus asked. Unlike the rest of them, the master was a child of The Lunar, so he slept during the day. He only woke if he wanted a Solar-zenith snack, or if his Avimimi had something to report. It was rather impractical, having a Lunar child as their master, but in their eyes he was not like the other Lunar children.

One popular warning for hatchlings (who were children of The Solar) from their parents was:

‘Your fate will come sooner

If you converse with a child of Lunar’

but the dinosaurs in the kingdom felt the master was an exception to the rule. He was gentle and kind, and looked out for them, scavenging from carcasses for food. He was very friendly and approachable, unlike most other children of The Lunar, it was thought.

The Avimimi entered the cave before establishing who was to rouse the master, and moved forward into the gloom of the cavern. Shadows smothered everything; The Solar’s light had not yet reached the inside of the cave; it only managed that at a few hours before Light Kalm, and at first the Avimimi, whose eyesight was quite poor anyway, could not see their master.

Once their eyes had adjusted, they saw a large bulk reclining in the far corner, moving gently up and down as it breathed. Its breath was soft and echoed quietly. The leader of the colony advanced forwards, squinting, and gave a polite cough. There was a low, rumbling growl, and the shape shifted for a moment, and then settled down again.

The Avimimus coughed again, louder, and this time there was a response. The master rose, to a height of twenty feet or so, and stretched. His head was boxy, with colossal jaws, and two limp, spindly forearms at his side. He was about thirty-six feet long. A Tarbosaurus.

The feathered insectivores stepped back as the master threw open his jaws and yawned. Blinking, he gazed out of the cave and across the landscape.

“My, my,” he mumbled, “is it Light Kalm already? Oh, wait, I can’t even see The Solar…is it still Dark Kalm?” Oh, I can’t even get to sleep any more…I…”

“No, Sire,” the leader piped up, “it’s pre-Solar-zenith. We’ve woken you to give you news of the hatches you asked for. Confirmation.”

“Sleek,” the Tarbosaur said irritably, “Don’t call me ‘Sire’. Right, yes, the hatches…” he yawned again and stepped out into the light. “…Good year, is it?”

“Exceedingly, Sire…I mean, Crow,” the leader corrected himself, “there are at least six hatchlings to every clutch, and all but one of the live head-butter births have been successful!”

“Wonderful, wonderful,” Crow nodded, still drowsy. He swayed on his feet unsteadily.

He was very dark in colour, brown but an almost bark-brown. Black meerkat stripes ran down his back, and his green eyes squinted in The Solar’s light. Unlike Vulcan, he was an adult Tarbosaur. He was still strong, yet not as strong as he had been when he had first taken over Ignis Springs and lived in Ignis Cave. He was admired and liked by everyone, with no exceptions.

“It’s almost Solar-zenith, Sire…Crow…,” the second Avimimus said hastily, “shall we send out another patrol?”

“What? Oh, yes, certainly. Is that all, Sleek?”

“Yes, Crow. We’ll send the others up with reports later, when you’re up and about.”

“Very well. Thank you.”

Then he turned and wobbled back into the cave and darkness.

“Don’t you ever have any doubts about this place?” Sleek asked his companion.

The other frowned. “What d’you mean?”

“You know, it’s like we’ve had it all too easy. No predators, apart from Crow, and those Oviraptors either eat shellfish or steal eggs. The occasional Pterosaur might take young, but apart from them, we haven’t got any real predators here. Crow tends to scavenge nowadays.”

“What, you’re saying it’s bad because we don’t have any ‘real’ predators, as you call it?”

“Well, I’m not sure. But surely there’s an imbalance somewhere. I don’t know…I suppose I’m just afraid this carefree life won’t last forever. Afraid that something, sooner or later, is going to come along and wreck it all!”

“Like a child of Lunar?”

“Perhaps.”

They fell into silence as they descended Ignis Peak. The Solar hung high at zenith, and the dinosaurs roamed beneath a cloudless sky. Shadows disappeared, and the herds groaned as the heat grew more intense, moving to bathe in the river or shelter beneath the trees. Some ventured into the outer fronds of the jungle, while others travelled over the hills beside Ignis Peak to drink from the lake that lay beyond. Sleek ruffled his feathers, muttering about lining them with water again to keep himself cool.

Once back on the ground, they headed towards the thorn scrub, where two of the sentries were posted. Others were posted at the jungle, hills and the cliffs, just watching should any new animals enter Ignis Springs, and generally keeping their eyes open. The idea of patrolling the area was one suggested by the Avimimi themselves; they were perhaps the most vulnerable of dinosaurs in the territory, and wanted to watch out in case any predators arrived on the scene that were unfamiliar to Ignis Springs.

Sleek and his companion were firstly going to report to each pair, inquiring of any unusual activities, or of course, new dinosaurs entering the kingdom, and then take over the shift. Other Avimimi would change with the current sentries, until Light Kalm, and again the shift would change. They arrived at the thorn scrub, picking their way through the prickly bushes and sand, towards the post. Two Avimimi were there, sat up in small trees, peering about. They gave a pleasant wave to the others as they advanced, and one of them jumped down from the tree.

“Solar-zenith, you two!” he greeted heartily.

“Solar-zenith,” Sleek smiled, “any news?”

The other shrugged, “Not much, only a couple of Oviraptors laying eggs. A bit late! Oh, and we saw a little group of Protos out in the desert, near the boundary line. They’re not from around here, though. Youngsters, probably last year’s clutch. They hovered about a bit, and then went away again.”

“There you are, you see?” Sleek’s companion nodded, “nothing to worry about.”

“We haven’t checked the other posts, yet,” Sleek said quietly.

“What’s wrong?” frowned the Avimimus up in the tree, “What’re you worried about, Sleek?”

“I don’t know,” he admitted, “It’s just that I’m worrie sooner or later, things are going to go wrong. Like new predators coming here and spoiling everything!”

“They haven’t come before,” said the other, “what makes you think they’ll come now?”

“I don’t know. Just a fret, I suppose, probably nothing in it.”

“Well, you two can go off duty, now,” Sleek’s companion changed the subject, “we’ll take over. Enjoy the zenith!”

“We will,” they replied as they headed back towards the plains.

The weeks went by. Day by day, Sleek’s fears were calmed, and the land was at peace, as it always had been. The terrain was overrun with hatchlings and offspring, scampering and playing, the exhausted parents grazing or dozing in the shade. There were several late layers, though. A couple of Oviraptors and Protoceratopi, were still expectant with eggs, and the job of counting them all had become extremely tedious for the Avimimi.

It was at Light Kalm, when some of the late layers’ eggs were being counted, that Sleek’s feared returned. They were at the thorn scrub, with a hen Oviraptor, Othelia, and her adopted son, a mammal named Zazlah, when the trouble arose.

Oviraptors were an odd-looking breed. Built like ostriches, they had long legs and necks. Their beaks were large and parrot-like, for cracking open not only eggs and fruit, but also shellfish they caught in the river. When the breeding season was over, the Oviraptors fed off shellfish instead of eggs, which they normally stole from other dinosaurs’ nests. Oviraptors were quite small, about four and a half feet tall when fully grown, sandy-yellow in colour, sometimes with a white underbelly and speckles, and a curious nasal bump and curved crest upon their heads.

“Five wonderful eggs,” Othelia smiled at Sleek, “the largest local Oviraptor clutch, I believe?”

“Yes, indeed. Congratulations. And where is the proud father?” The Avimimus ventured to ask, but bit his lip in case the reply was negative.

“Oh, him?” Othelia wrinkled her nose, “he’s gone off to get me some food. Lazy so ‘n’ so, he only does it after I nag him for ages.”

“Oh, I’m sure he’s just eager to hang around and look at your lovely eggs,” Sleek said good-naturedly, “what a sight they are. When will they hatch?”

“In a few weeks,” Othelia replied happily, gazing down at Sleek from her great height, despite her reclining in the nest. He reciprocated the smile and awaited the father’s return.

Meanwhile, the father of the clutch, a cock Oviraptor named Filcher, was busy searching the thorn scrub for any unguarded nests of eggs. He would have gone to the river to catch some shellfish instead – it would certainly have been easier to do that – but all Her Ladyship wanted was eggs for supper. So, out he had been sent to find just that.

He looked uneasily to the west, where The Solar was sinking beneath The Sky Mirror, its reflection on the waves shimmering in golden crescents. He disliked being out so late; he was a child of The Solar, and usually by now all the children of light should be heading home to sleep or roost. Although there were no carnivorous Lunar children – besides Crow – in Ignis Springs, Filcher still found the hours of dark threatening, especially when it was a Dark Zenith.

He was torn between heading back and taking one last look for some eggs; if he went home empty handed he would have to put up with a raging headache for several days from Othelia, but it was almost bearable compared to being out in a Dark Zenith. He shrugged, and was about to return to the nest when something caught his attention.

A shadow was prowling about at the edge of the thorn scrub, where the plains went off into the hills beside the mountain range. The figure was slinking about, peering around and generally looking suspicious. Filcher instantly dived behind a prickly bush. Half fearfully, he gazed over the top, watching the stranger.

It was built a little like himself, yet more serpentine, and only about three feet high. It had a long neck and snout, and large blotches on each side of its head. On each big toe – Filcher shivered as he looked – there was a sickle-like claw, bigger than the others, which was held high off the dusty ground.

Filcher was half terrified and half fascinated. He had never seen this kind of creature before, and was mystified as to what it was or what it was doing here. His first thought was to report it to a sentry, but his curiosity got the better of him and he found himself, ever so quietly, slipping between the bushes towards the unknown animal.

As it looked up, Filcher ducked down and then realised that the huge blotches on either side of its head were its eyes. He gasped; he had never seen eyes so big before! They were serpentine and stabbed out at him viciously. At this, Filcher confirmed that he had never come across this dinosaur in Ignis Springs, and he doubted whether anyone else had.

The dinosaur snorted, and then turned, heading for the foot of Ignis Peak. Astonished, Filcher followed, keeping to the shadows. Surely one of the sentries must have seen it? The Oviraptor watched in amazement as the animal slowly began to climb the dead volcano. It skipped up the rocks with ease, using its lethal-looking claws for grip. It was heading towards Ignis Cave.

Filcher emerged from the thorn scrub, and crouched behind a cycad-palm. Well, at least Crow’ll take care of it, he thought, it’s Light Kalm, he should be up by now. But still he could not take his eyes away from the stranger. After a good few minutes of climbing, the shadow alighted upon the ledge before the mouth of Ignis Cave.

This’ll be good, the Oviraptor thought with a chuckle, if he goes in he’ll be eaten up right away! He won’t know what hit him!

But the dinosaur remained outside. It turned its head, listening to the sounds in the cave. Then it sniffed the ground before it, then up the wall beside the mouth, then up in the air, and then down the other wall, in a semi-circle, before once again putting its ear to the entrance. As if satisfied, the creature nodded to itself, and began to descend the mountain.

Filcher, alarmed, dived back towards the thorn scrub and hid behind a bush, cowering away. As the animal stepped upon the ground once more, it took one last look around before heading back towards the hills.

Thorne slipped away, into the shadows of the Light Kalm, to report to his master.